Thirty two years after my grand tour of Europe I’m finding myself reading The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone for a second time. I read it between destinations and it proved to be a wonderful tome for touring Italy and experiencing masterpieces from the Renaissance. Reading it again I’m finding it an encouragement as an architect in my fifties. I totally missed the agony Michelangelo experienced. It’s not that I didn’t understand the frustration and struggle he went through to create his wonderful works, but in my early twenties I was in college and dating my future wife. I had nothing but hope before me. Before me was the ecstasy of being an architect—producing works of architecture that would move hearts. Now I understand viscerally the agony of this profession. Please don’t misunderstand me—this is a good career and very fulfilling, but now I understand the pain and frustration that goes along with it. Now as I read this historical novel I feel what Michelangelo must have felt when moving from rags to riches and back to rags. I understand what Michelangelo must have struggled with when he wrestled with taking a commission just to pay the bills. I know what Michelangelo must have been thinking when he had to deal with unreasonable clients. If you’ve been in the architecture profession for decades this is a good read. It will encourage you that you are not alone--even the greatest of artists struggled in their quest to create good works. It will encourage you to press on through the agony and the ecstasy of a completing your work will come in time.

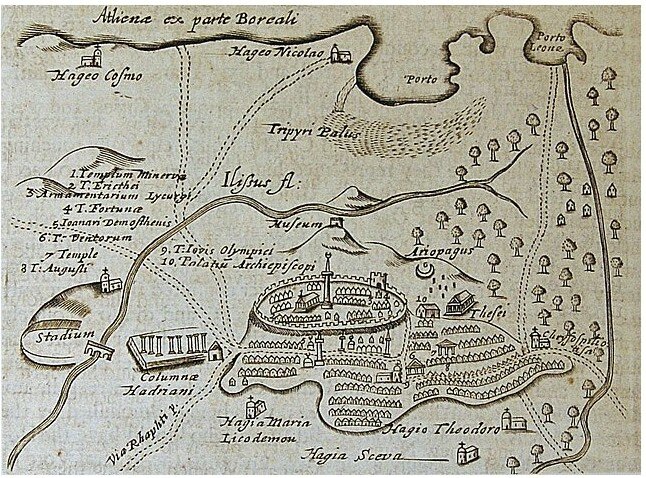

My paperback from my European Grand Tour